Reading the Eyes in the Mind Test

- Research

- Open up Access

- Published:

Examination-retest reliability of the 'Reading the Heed in the Optics' test: a one-year follow-up study

Molecular Autism volume 4, Article number:33 (2013) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

The 'Reading the Mind in the Eyes' (Eyes) test is an avant-garde test of theory of mind. Information technology is widely used to assess individual differences in social knowledge and emotion recognition across different groups and cultures. The nowadays study examined distributions of responses and scores on a Spanish version of the exam in a non-clinical Spanish adult population, and assessed exam-retest reliability over a 1-year interval.

Methods

A full of 358 undergraduates of both sexes, age eighteen to 65 years, completed the Spanish version of the exam twice over an interval of 1 twelvemonth. The Bland-Altman method was used to calculate exam-retest reliability.

Results

Distributions of responses and scores were optimal. Test-retest reliability for total score on the Optics test was .63 (P <.01), based on the intraclass correlation coefficient. Test-retest reliability using the Bland-Altman method was fairly good.

Conclusions

This is the offset written report providing testify that the Eyes test is reliable and stable over a 1-twelvemonth period, in a non-clinical sample of adults.

Background

Psychology researchers accept adult reliable instruments for evaluating social cognition and emotional and social processing in both the laboratory and the dispensary [1]. Social cognitive studies examine how people procedure information in the social surroundings, especially perceiving, interpreting, and responding to the mental states (intentions, feelings, perception, and beliefs), dispositions, and behaviors of others [2–5]. These processes are tightly linked to processes referred to as emotion recognition and 'theory of listen', that allow individuals to imagine the mental land of others [6] to both predict their behavior and reply accordingly. Numerous studies have shown that deficits in emotion recognition and theory of mind compromise social interaction and are related to conditions such as schizophrenia [7, 8], autism [9–11], eating disorders [12–fourteen], bipolar disorder [15, 16], social feet [17], and borderline personality disorder [18].

Different instruments have been developed to assess deficits in social cognition in adults. Instruments designed to appraise emotion recognition require the private to identify emotions and their intensity on the ground of different stimuli, such as facial expressions in the 'facial emotion identification task' [19], spoken phrases in the 'Reading the Listen in the Vocalism' examination [twenty] or computer-generated, distorted facial pictures (morphing) [21]. Instruments to assess theory of mind, in contrast, oftentimes crave individuals to read brusk stories and answer questions about them [22]. These instruments are intended to assess theory of mind in individuals with autism or Asperger Syndrome, but may too be applicable to other conditions [23].

To provide more detailed information about theory of mind dysfunction, Businesswoman-Cohen et al. developed the 'Reading the Mind in the Optics' examination, an advanced test of theory of mind [23]. The first version consisted of 25 photographs of actors and actresses showing the facial region around the eyes. The participant is asked to choose which of two words all-time describes what the person in the photograph is thinking or feeling. These words refer to both basic mental states (for instance, 'happy') and circuitous mental states (for example, 'arrogant') [23]. In this fashion, the Eyes exam aimed to evaluate social cognition in adults past assessing their ability to recognize the mental state of others using just the expressions around the eyes, which are key in determining mental states [24].

The original 'Reading the Mind in the Optics' test had some limitations because the number of items and the binomial response format did not sufficiently differentiate individuals receiving higher scores. Thus a revised 'Reading the Heed in the Eyes' test was created, in which the number of items was increased to 36 and the number of possible responses (single-give-and-take descriptors of possible mental states) was increased to four, reducing the maximum correct judge rate to 25% [1]. The possible mental state descriptors refer by and large to complex mental states. This avant-garde test was designed to take sufficient analytical complexity to be appropriate for adults with and without psychopathology, brain damage or dementia, to assess factors that might contribute to social difficulties. In this way, the examination is intended to let assessment of social knowledge in an adult population with average intelligence.

Although conceived every bit an avant-garde theory of heed examination [1], the Eyes examination is also used to assess emotion recognition. Completing the instrument requires not only the power to recognize emotional expressions but also the ability to determine the complex cognitive mental state of an individual based on a partial facial expression. Together, these abilities presuppose that the private possesses a mental country lexicon and knows the significant of mental state terms [1].

Studies of social noesis impairments in clinical populations evidence that typical individuals score significantly higher on the Eyes examination than do individuals with schizophrenia [7, eight], autism [9, 10], eating disorders [12, 13, 25], and social feet [17] (for a review, see [26]). These studies betoken that the Eyes test is reliable for assessing social cognition in adults. The Eyes test has likewise proven useful for assessing social intelligence and its subtle impairment in different cultures, as shown in studies using translations of the Eyes test into Turkish, Hungarian, Japanese, French, German, and Argentinian Spanish [seven, 27–31].

Most studies with the Eyes test take not reported information on test-retest reliability [26]. This is essential because the Eyes test, like tests explicitly designed to test emotion recognition [32], has psychometric properties that foreclose straightforward calculation of Cronbach's alpha. Calculating this parameter is complex because researchers are express to comparing the number of right responses between individuals. Thus, many studies involving the Optics examination exercise not include Cronbach's alpha, making it impossible to draw reliable intergroup comparisons, such equally comparisons between clinical and control groups or comparisons between the same group before and later an intervention. Intergroup comparisons are also important for cross-cultural studies, which aim to test if cultures differ more than in how they identify circuitous mental states than simpler mental states [26]. Such studies are of import for indicating whether the Eyes test should be adjusted specifically for different cultures.

Recent studies have addressed this gap by reporting acceptable test-retest stability for the adult version of the Optics test [26, 33] every bit well as for the child version [34]. The time intervals for retesting in these studies were relatively short, ranging from 2 weeks to 1 month. In order to provide the offset assessment of long-term test-retest reliability of the Eyes test, likewise equally the first detailed validation of the examination in a Castilian population, the nowadays study (1) examined the distribution of responses and scores on a Spanish version of the Optics examination in a nonclinical Spanish population, and (2) assessed the 1-year test-retest reliability.

Method

Participants

A total of 358 outset-yr psychology undergraduates enrolled at the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED, Spain) took part. The sample comprised 75 men and 283 women, with a mean age at the first testing of 34.23 years (sd, 9.02; range, 18 to 65). This bias toward female person participants merely reflects the sex ratio in those who choose to study psychology at the undergraduate level. All participants were volunteers who gave written informed consent and who received personalized reports of results at the end of the study. The study was carried out in accordance with the Annunciation of Helsinki. Ideals approval was obtained from the Enquiry Ethics Commission, UNED.

Procedure

The offset testing took place during May and June 2011; the 2nd testing took place during the same months in 2012. During both testing sessions, the survey was administered using a computer program that recorded identification data for each participant, displayed test items and saved the responses.

Measures

The revised Eyes test [i] was used to generate a Castilian version of the Eyes examination. Ii translators, both with PhDs in psychology and experts in cognition and emotion, created a Spanish version of the musical instrument, which was then dorsum-translated into English language by 2 contained translators. In this version, as in the English language-language original, participants were shown 36 photographs of middle regions of individuals and asked, for each photograph, to choose one of 4 possible words to depict the mental state of the person shown. One point was assigned for each right response, then scores could range from 0 to 36. This Castilian version is available from the authors on asking.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 19.0. (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). The Banal-Altman plot to compare examination and retest results was calculated using the MedCalc program, version 12.3 (MedCalc™, Mariakerke, Kingdom of belgium, http://www.medcalc.be). All tests were two-tailed and were conducted at the 5% level of statistical significance.

Results

Tabular array 1 shows the correct respond for each particular on the Spanish version of the Optics examination, and the percentages of participants that selected each answer on the exam and retest.

Virtually all items on the examination were answered correctly by more than 50% of participants. The only exception was item 19, which was answered correctly past only 39.0% of respondents during the test and by only 40.4% during the retest. The next virtually frequently selected answer B was chosen by 36.two% and 34.4% of respondents during testing and retesting, respectively. The mean percentage of items correctly answered was 75.51% on the test and 75.46% on the retest. There were no significant differences in the percentages of respondents choosing the right reply across all items during testing and retesting (t = .093, P <.926). In fact, for all items, the correct answer was chosen far more often than the adjacent almost frequently selected choice.

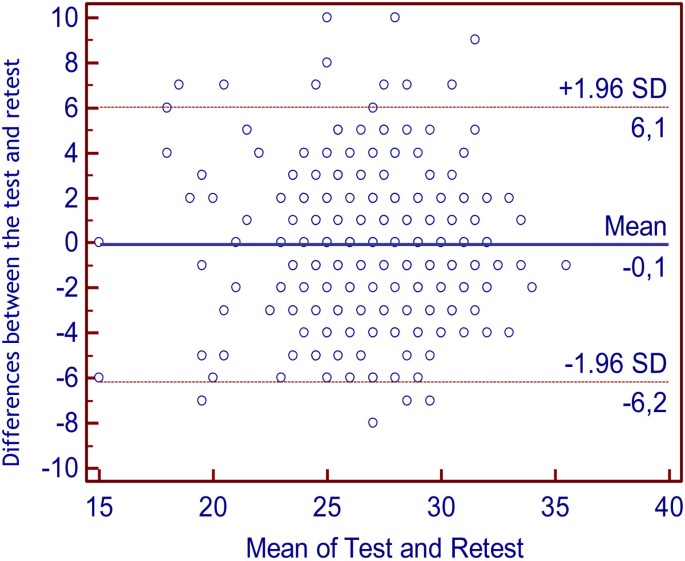

Converting the hateful percentages above to the 0 to 36 calibration of the Eyes test gave hateful point scores of 27.18 (sd = iii.59) on the examination and 27.24 (sd = three.67) on the retest (t = .36, P <.722). Test-retest stability was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which was .63 for the full score (P <.01). Table two shows test-retest correlations for each of the items. Correlations for all items except detail 18 were positive and significant. Although results for item 18 showed 330 of 358 possible coincidences, no pregnant linear correlation was establish. This consequence does not mean that test and retest results for item 18 were independent, but rather that they were non linearly related. The Bland-Altman plot [35] was used to examine test-retest concordance. This graphical arroyo allows for the examination of the agreement between repeated measurements by plotting the differences between examination and retest scores against the hateful value of the examination and retest scores for each participant. Conviction intervals for the mean difference are calculated to determine if the mean difference deviates significantly from zero (Figure 1).

Bland-Altman plot of the eyes test-retest assessment (n) = 358.

The mean difference between test and retest responses across all participants was −0.06 (SD = 3.12), indicating no significant change in results betwixt testing and retesting i year later on. The 95% conviction interval (CI) for the mean difference was −6.17 to 6.05; thus, the CI included 0. Most results fell within the 95% CI, and those that did not failed to show any tendency, suggesting that they reflected take chances variation. Estimated measurement error based on within-subject standard deviation was 3.63, and the coefficient of repeatability was six.24.

Discussion

The primary purpose of the electric current study was to examine the long-term reliability of the Castilian translation of the Eyes test in Spain. To our noesis, this is the first report providing evidence that the Eyes exam is reliable and stable over a 1-year flow in a nonclinical population sample. To determine the reliability of the Spanish version of the Eye exam, nosotros analyzed the distribution of responses for each item during testing and retesting 1 year later. The results indicate that not all items are equally difficult, which should increase the discriminant ability of the test. The distribution of difficulty across all items of the examination was approximately normal and greater than 50% for the correct response. Despite the fact that less than 50% of the respondents correctly answered item xix, the majority did in fact cull the right respond. In the Italian version of Eyes test like percentages were obtained [26]. Further research should exist conducted to determine if the item should be eliminated due to ambiguity or retained because it is difficult, and therefore useful in testing emotional discrimination.

Test-retest reliability using the ICC indicated a pregnant correlation between the total scores on the test and retest, demonstrating that results were stable over time. They as well indicate that no learning occurred in the written report population [34]. Item-by-item correlation analysis between test and retest showed that responses to all items except particular 18 were stable over time. This finding implies that emotion recognition judgments, both correct and incorrect, persist over fourth dimension. The relatively long interval of 1 twelvemonth between test and retest farther suggests that such persistence is non due to adventure but to the existence of stable cerebral dispositions in recognizing circuitous emotions [ane].

We used the graphical method of Bland-Altman to assess test-retest cyclopedia on our Spanish translation of the Optics examination. This approach allowed us to analyze the position of test-retest differences relative to the exam-retest mean. This analysis showed that most responses on all items were concordant with one another; mean differences were 0, and most differences roughshod within the 95% CI. The differences were homogeneous and appeared to be distributed randomly across all items of the examination, with no bear witness of a systematic bias or tendency. The small differences and their homogeneity lead us to conclude that the Eyes test is reliable and stable for up to 1 year, not only with respect to total scores simply also to the distributions of answers for each item. These results may help guide the identification of items that discriminate betwixt clinical and nonclinical populations in further studies.

This report is not without limitations. Commencement, the proportion of women in our test population was much higher than that of men, raising the possibility of gender bias. 2d, this written report examined test-retest reliability over a relatively long period of 1 yr. Hereafter studies should likewise investigate the stability of the Spanish version over shorter fourth dimension periods, since stability is expected to be greater over shorter periods [26].

Several studies using Optics test accept analyzed gender and historic period differences without conclusive results [26]. Our written report did non accost these bug. Time to come studies should investigate these differences and explore the mechanisms by which gender and age influence the evolution of theory of mind and emotional recognition. Additionally, it would be interesting to examine how other objective measures of emotion recognition, empathy, and emotional intelligence are related with Optics test.

Numerous international studies using the Eyes exam have shown group differences in emotion recognition and theory of listen betwixt individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia [vii, 8] or autism [9–11] and typical command groups. The Spanish version of the Optics test will help in the diagnosis and constructive implementation of intervention programs for individuals with damage in social knowledge in Castilian-speaking countries. This exam will let the comparison of an individual's score with the normative scores of Spanish samples and will enable researchers and clinicians to describe with accuracy any change of their scores before and after intervention programs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results from the current study advise that the Eyes test is a reliable measure of theory of heed and recognition of complex emotions in adults, and that it is stable over a 1-year period in a nonclinical population. This Spanish version of the Optics examination will be useful in future inquiry into social knowledge in laboratory and clinical contexts, including cross-cultural and clinical investigations into autism and related neurodevelopmental conditions, in Spain and in other Spanish-speaking countries.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- sd:

-

Standard deviation.

References

-

Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Loma J, Raste Y, Plumb I: The "reading the mind in the optics" test revised version: a report with normal adults, and adults with asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J Kid Psychol Psychiatry. 2001, 42: 241-251. 10.1111/1469-7610.00715.

-

Brothers Fifty: The neural basis of primate social communication. Motiv Emot. 1990, 14: 81-91. 10.1007/BF00991637.

-

Fiske ST, Taylor SE: Social cognition: From brains to culture. 2013, London, UK: SAGE Publications Limited

-

Kunda Z: Social cognition: Making sense of people. 1999, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press

-

Baron-Cohen Due south: Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind. 1995, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

-

Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Perkins DO, Lieberman J: Implications for the neural footing of social cognition for the study of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003, 160: 815-824. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.five.815.

-

De Achával D, Costanzo EY, Villarreal M, Jáuregui IO, Chiodi A, Castro MN, Fahrer RD, Leiguarda RC, Chu EM, Guinjoan SM: Emotion processing and theory of mind in schizophrenia patients and their unaffected first-caste relatives. Neuropsychologia. 2010, 48: 1209-1215. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.12.019.

-

Green MF, Olivier B, Crawley JN, Penn DL, Silverstein S: Social cognition in schizophrenia: recommendations from the measurement and treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia new approaches conference. Schizophr Balderdash. 2005, 31: 882-887. 10.1093/schbul/sbi049.

-

Baron-Cohen Due south: Essential Deviation: Men, women and the extreme male brain. 2003, London, UK: Penguin

-

Baron-Cohen Southward: Autism: the empathizing-systemizing (Due east-S) theory. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009, 1156: 68-80. ten.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04467.10.

-

Lombardo MV, Chakrabarti B, Lai Grand-C, Baron-Cohen S: Cocky-referential and social cognition in a case of autism and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Mol Autism. 2012, 3: 14-10.1186/2040-2392-3-14.

-

Adenzato Yard, Todisco P, Ardito RB: Social cognition in anorexia nervosa: bear witness of preserved theory of listen and impaired emotional operation. PloS one. 2012, vii: e44414-10.1371/journal.pone.0044414.

-

Harrison A, Tchanturia K, Treasure J: Attentional bias, emotion recognition, and emotion regulation in anorexia: state or trait?. Biol Psychiatry. 2010, 68: 755-761. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.037.

-

Baron-Cohen S, Jaffa T, Davies S, Auyeung B, Allison C, Wheelwright South: Do girls with anorexia nervosa have elevated autistic traits?. Mol Autism. 2013, 4: 24-

-

Derntl B, Seidel E-M, Kryspin-Exner I, Hasmann A, Dobmeier M: Facial emotion recognition in patients with bipolar I and bipolar Two disorder. Br J Clinical Psychol. 2009, 48: 363-375. 10.1348/014466509X404845.

-

Ryu V, An SK, Jo HH, Cho HS: Decreased P3 amplitudes elicited past negative facial emotion in manic patients: selective deficits in emotional processing. Neurosci Lett. 2010, 481: 92-96. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.06.059.

-

Machado-de-Sousa JP, Arrais KC, Alves NT, Chagas MHN, de Meneses-Gaya C, Crippa JADS, Hallak JEC: Facial impact processing in social anxiety: tasks and stimuli. J Neurosci Methods. 2010, 193: 1-6. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.08.013.

-

Frick C, Lang S, Kotchoubey B, Sieswerda Southward, Dinu-Biringer R, Berger One thousand, Veser South, Essig M, Barnow South: Hypersensitivity in borderline personality disorder during mindreading. PLoS One. 2012, vii: e41650-10.1371/journal.pone.0041650.

-

Ihnen GH, Penn DL, Corrigan PW, Martin J: Social perception and social skill in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1998, eighty: 275-286. 10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00079-1.

-

Rutherford MD, Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S: Reading the listen in the vox: a study with normal adults and adults with asperger syndrome and high operation autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2002, 32: 189-194. ten.1023/A:1015497629971.

-

Scrimin South, Moscardino U, Capello F, Altoè G, Axia 1000: Recognition of facial expressions of mixed emotions in school-age children exposed to terrorism. Dev Psychol. 2009, 45: 1341-1352.

-

White Due south, Loma E, Happé F, Frith U: Revisiting the foreign stories: revealing mentalizing impairments in autism. Child Dev. 2009, 80: 1097-1117. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01319.x.

-

Businesswoman-Cohen South, Jolliffe T, Mortimore C, Robertson M: Another advanced test of theory of mind: evidence from very high functioning adults with autism or asperger syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997, 38: 813-822. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01599.x.

-

Adams RB, Rule NO, Franklin RG, Wang East, Stevenson MT, Yoshikawa Southward, Nomura Yard, Sato W, Kveraga K, Ambady North: Cross-cultural reading the heed in the eyes: an fMRI investigation. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010, 22: 97-108. 10.1162/jocn.2009.21187.

-

Medina-Pradas C, Blas Navarro J, Alvarez-Moya EM, Grau A, Obiols JE: Emotional theory of mind in eating disorders. Int J Clin Heal Psychol. 2012, 12: 189-202.

-

Vellante Yard, Baron-Cohen S, Melis One thousand, Marrone M, Petretto DR, Masala C, Preti A: The "reading the mind in the eyes" test: systematic review of psychometric properties and a validation study in italy. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2012, 18: 326-354.

-

Bora Eastward, Vahip S, Gonul Equally, Akdeniz F, Alkan One thousand, Ogut M, Eryavuz A: Show for theory of heed deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005, 112: 110-116. x.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00570.x.

-

Havet-Thomassin V, Allain P, Etcharry-Bouyx F, Le Gall D: What nearly theory of mind afterward severe brain injury?. Encephalon Inj. 2006, twenty: 83-91. 10.1080/02699050500340655.

-

Kelemen O, Kéri S, Must A, Benedek Grand, Janka Z: No prove for dumb "theory of mind" in unaffected offset-degree relatives of schizophrenia patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004, 110: 146-149. x.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00357.x.

-

Kunihira Y, Senju A, Dairoku H, Wakabayashi A, Hasegawa T: "Autistic" traits in non-autistic Japanese populations: relationships with personality traits and cognitive power. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006, 36: 553-566. 10.1007/s10803-006-0094-i.

-

Voracek 1000, Dressler SG: Lack of correlation between digit ratio (2D:4D) and Baron-Cohen'south "reading the mind in the optics" test, empathy, systemising, and autism-spectrum quotients in a general population sample. Personal Individ Differ. 2006, 41: 1481-1491. 10.1016/j.paid.2006.06.009.

-

Bänziger T, Scherer KR, Hall JA, Rosenthal R: Introducing the MiniPONS: a short multichannel version of the profile of nonverbal sensitivity (PONS). J Nonverbal Behav. 2011, 35: 189-204. 10.1007/s10919-011-0108-3.

-

Yildirim EA, KaŞar Grand, Güdük M, AteŞ Due east, Küçükparlak I, Özalmete EO: Investigation of the reliability of the "reading the mind in the optics test" in a turkish population. Turkish J Psychiatry. 2011, 22: 177-186.

-

Hallerbäck MU, Lugnegård T, Hjärthag F, Gillberg C: The reading the mind in the eyes test: test-retest reliability of a Swedish version. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2009, 14: 127-143. x.1080/13546800902901518.

-

Bland JM, Altman DG: Statistical methods for assessing agreement betwixt two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986, i: 307-310.

Acknowledgements

RC and PFB were supported in function past project SEJ-03036 from the Department of Economic science, Science, and Business, Junta Andalucia (Kingdom of spain). SBC was supported by the European union, the MRC, and the Wellcome Trust during the menstruation of this work. He was part of the NIHR CLAHRC for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust.

Author information

Affiliations

Respective writer

Additional data

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

EGFA conceived of the study, participated in the data collection, analyzed the data and led preparation of the manuscript. RC and PFB conceived of the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SBC contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the estimation of data, helped to draft and revise the manuscript and have read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is published under license to BioMed Primal Ltd. This is an Open Access commodity is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ii.0 ), which permits unrestricted utilise, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Fernández-Abascal, E.G., Cabello, R., Fernández-Berrocal, P. et al. Test-retest reliability of the 'Reading the Mind in the Eyes' test: a i-year follow-up study. Molecular Autism iv, 33 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2040-2392-iv-33

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/2040-2392-4-33

Keywords

- Reading the mind in the eyes

- Reliability

- Assessment

- Social knowledge

- Theory of heed

massenburgarly1977.blogspot.com

Source: https://molecularautism.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2040-2392-4-33

0 Response to "Reading the Eyes in the Mind Test"

Post a Comment